- “Though we travel the world over to find the beautiful we must carry it with us or we find it not.”

- -Ralph Waldo Emerson

“The New Shape in Fashion” was the slogan of MODE, a revolutionary fashion magazine for “plus sizes.” This slogan was quite ironic, however, because the kind of beauty that MODE promoted was not “new” at all. Neither was it in any way dated. In fact, it was timeless—something which becomes abundantly clear when we compare today’s plus-size models with the most revered icons of female beauty in Western history.

THE CLASSICAL ERA

THE CLASSICAL ERA

Barbara Brickner and “Winged Victory”

Barbara Brickner may be the most perfectly-proportioned woman in the world, and could certainly have been the model for Winged Victory, c. 200–190 B.C. (also known as the Nike of Samothrace), one of the most celebrated of all classical sculptures. We see here the historical justification for referring to plus-size models as “goddesses.”

THE EARLY RENAISSANCE

THE EARLY RENAISSANCE

Shannon Marie and Simonetta Vespucci

Even in our own day and age, which is so hostile to true beauty, we still praise the charms of a woman with “Botticelli curves.” But have you ever gazed at Botticelli’s famous masterpiece, The Birth of Venus, and wondered what mortal woman could ever have served as the model for a goddess of such opulent perfection? The answer is Simonetta Vespucci (1453–1476), the cousin of the famous Florentine explorer, Amerigo Vespucci. The portrait of Simonetta shown here is also by Botticelli, from the National Gallery in Berlin.

“La bella Simonetta,” as she was called during her lifetime, was more than just the loveliest woman in Florence. Just as Helen of Troy had been the symbol of all that was great in Greek civilization, so, as Renaissance scholar Robert de la Sizerane tells us, Simonetta was “the Renaissance typified in a woman, the nymph of antiquity who breathed and walked and spoke a language of fancy and liberty.” Sandro Botticelli was still a young man when he first laid eyes on Simonetta, and the effect of her beauty was so powerful, as Sizerane puts it, that “on the wax of his imagination, still soft, Botticelli received the impression of an ideal which was destined never to be effaced.” For the rest of his career, he “painted no one but her. His Madonnas, his Venuses, his allegories—all were taken from her.”

Simonetta’s divine beauty inspired other immortal tributes as well. Countless poems and canvasses (by many painters besides Botticelli) were created in her honour. Every nobleman in Florence was besotted with her, even the brothers Lorenzo and Guilano of the famous Florentine ruling family, the Medicis. Lorenzo de Medici was occupied with affairs of state, but Guilano became her vassal, and, like something out of a fairytale, organized a jousting tournament in her honour. Guiliano entered the lists bearing a banner on which was a picture of Simonetta (painted by Botticelli himself), beneath which was the French inscription, “La Sans Pareille” (the unparalleled one). “The whole of Florence,” we read, “proudly saw itself mirrored in this couple, these perfect types of humanity which its effort towards the Beautiful had produced.” Tragically, Simonetta died young, but the memory of beauty lived on. Thirty-four years later, Botticelli asked to be buried at her feet.

Just as the Renaissance heralded the reawakening of Western interest in classical art and learning, so it is said that the arrival of Simonetta Vespucci “marked the return of fantasy into the world.” In our own day and age, the dazzling Shannon Marie likewise appears to have emerged from a fairytale, so many features does she share with “La bella Simonetta,” including her golden tresses, prominent cheekbones, full red lips, the hint of a double chin, and the swelling, pear-shaped curves to which Renaissance artists paid homage in hundreds of paintings. Who would not wish to compose poems in praise of Shannon Marie’s beauty, or paint her as the goddess of love, or do battle for her honour in knightly combat? She, like her Florentine predecessor, reminds us of Goethe’s famous dictum that “the eternal Feminine always leads us higher.”

THE HIGH RENAISSANCE

THE HIGH RENAISSANCE

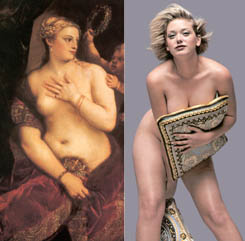

Titian’s Venus and Lara Johnson

Titian (1485–1576) is generally ranked with Michaelangelo and Raphael as the greatest painter of the High Renaissance. But whereas Michaelangelo perfected the masculine ideal, Titian’s genius was most conspicuous in his female subjects, and his sumptuous representations of femininity have never been equalled.

Titian’s most notable early celebration of the female figure was the Venus of Urbino, a reinterpretation of Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus motif. But Titian’s goddess (her disrobed state indicates her divine nature) is less idealized than Giorgione’s. Awake and aware, she meets her viewer’s gaze with intelligence and serene vanity. Later in his career, Titian found inspiration in an even lovelier and noticeably heavier fair-haired model, who personified for him the very acme of feminine beauty. The identity of this model is uncertain, but she is often judged the most beautiful woman in history. Titian first painted her in two mythological subjects, Danaë receiving the Golden Rain and Venus with Organist and Cupid, but his final representation of his fair muse in Venus with a Mirror (above) surpassed all his previous efforts, and ranks as Titian’s supreme masterwork. The artist was so attached to this painting that could never bear to sell it, and it remained with him until his death.

Unlike the earlier works, in Venus with a Mirror Titian’s voluptuous model adopts the classical pose known as the Venus Pudica, or “modest Venus.” But Titian contrasts the traditional modesty of the pose with the unmistakable pleasure in her own appearance that the goddess exhibits as she looks into the mirror—as if her luxurious charms are so wondrous that she herself is forced to pause and catch her breath in awe. In the parallel image above, we see Lara Johnson in the classical “modest” pose of Venus with a Mirror, but with one feature borrowed from the earlier Venus of Urbino—her challenging, confident scrutiny of her viewer. The most attractive model of her generation, Lara bears an uncanny resemblance to Titian’s preternaturally beautiful fair-haired muse, and deserves limitless veneration as a living reincarnation of a timeless feminine ideal.

THE BAROQUE ERA

THE BAROQUE ERA

Kate Dillon and Hélène Fourment

Late in his life, Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) fell helplessly in love with sixteen-year-old Hélène Fourment, and eventually married her. His new wife became his love and inspiration, serving as the model for most of the paintings that he executed in the last, most fertile phase of his career.

The image shown here, Venus before the Mirror, is the greatest depiction of female beauty in Western art. The subject of the love goddess entranced by her own reflection was a commonplace in the Renaissance and Baroque eras, and Titian’s Venus with a Mirror (see above) was considered the very pinnacle of the genre. That painting so captivated Rubens that he made a nearly literal copy for himself—which, however, fell short of Titian’s mastery. But in the subsequent Venus before the Mirror shown here, Rubens reinterpreted and personalized the theme according to the spirit of the Northern Baroque, and in doing so transcended his predecessor’s achievement. Rubens’s Venus is more humanized than Titian’s. Her figure is even fuller and more curvaceous, her unbound golden tresses cascade freely down her back, and she gazes, not upon her own reflection, but on how her beauty affects the viewer. But what is truly uncanny about this painting is that although it actually dates from 1614, it is a perfect likeness of Hélène. As Rubens scholar Bouchot-Saupique notes,

In some of Rubens’ early works, painted before his second wife was born, we can observe a curious fact; they often depict a fair, buxom, extremely sensual young woman remarkably like the one he was to meet and marry many years later.

Like a Jungian archetype, Hélène’s image was graven in Rubens’s heart throughout his life. And it is a great testament to Kate Dillon’s loveliness that, when she is at her most radiant, she seems to be a reincarnation of this wondrous beauty.

THE ROCOCO ERA

THE ROCOCO ERA

Boucher’s Europa and Tracie Stern

Derived from a term in French aesthetic history (rocaille), “Rococo” refers the style of art that followed the Baroque era and preceded Neoclassicism. The central figure of the Rococo was François Boucher (1703–1770), court painter to Louis XV and the personal favourite of the king’s mistress, Madame de Pompadour. Boucher’s work is an endless succession of depictions of mythological paradises in which pretty, full-figured goddesses take centre stage amidst lush backgrounds of intoxicating splendour.

Working largely for aristocratic audiences, Rococo artists like Boucher turned away from the dark solemnity and occasional horrors of the Christian subjects that had dominated the Baroque era, and towards Arcadian visions of pleasure and delight, the object of which was to stimulate…pleasure and delight. The art of the Rococo is therefore self-consciously decorative rather than utilitarian, its goal to elevate man above the drudgery of the mundane world in which he finds himself.

But expressions of beauty free from moral strictures always find voices of opposition. Seeing an opportunity to capitalize on the waning of religious morality in art, certain individuals in 18th-century France sought to impose upon art a new morality based on political grounds. Boucher was the target of the fiercest attacks, and his most relentless critic was Denis Diderot, one of the Philosophes whose work led France towards the butchery of the French Revolution.

To study the attitude of Diderot towards Boucher is to uncover a genealogy of morality as applied to the female figure. As noted in a fascinating new book titled Diderot and the Body, the Philosophe had oppressive “moral objections to voluptuousness.” Praising works in which the “robust fleshiness of Boucher has been bypassed,” Diderot considered beauty a offense unless it served a utilitarian purpose. Diderot wrote that the “concept of beauty should be redefined in terms of suitability for performing a particular task” and levelled the criticism against Boucher’s figures that “You will not find one engaged in any activity related to real life: studying lessons, reading, writing, beating flax. They are fanciful, imaginary creatures” (fancy and imagination obviously not being considered part of “real life”).

To anyone acquainted with modern weight-control propaganda, this line of thinking is all too familiar.

In excoriating Boucher for his lack of “delicacy, decency, innocence, and simplicity,” Diderot yoked those concepts together and assigned, for the first time, a moral value to minimalism and an immoral quality to opulence, both generally in aesthetics, and particularly in the depiction of the female figure. But Diderot’s real intention was to overthrow the French aristocracy, abolish the monarchy, and impose a new form of government (naturally with “englightened” thinkers such as himself in charge). Diderot’s wish to manipulate the female body was merely part of his drive to manipulate the body politic. It was a will to power.

Not surprisingly, we see this utilitarian assault on aesthetics rear its ugly head again in the era of Soviet despotism (“bourgeois decadence”), and also in the feminist ideology of the latter half of the twentieth century (“pariarchal objectification”). The terms change, the goal—a power grab—remains the same. Beware of any institution that attempts to deny or decry the power of beauty, or subvert it for its own political ends.

But Boucher’s vision of beauty weathered Diderot’s self-interested attacks, and has passed down to us intact as a perfect expression of an alternative reality of grace and splendour. That vision of beauty is reincarnated in Tracie Stern, who exhibits the round, cherubic facial features and voluptuous curves that characterized Boucher’s loveliest goddesses, and particularly Europa, his most gorgeous creation, as seen in his magnum opus The Rape of Europa. (You can read about the mythological basis for this painting here.) Mrs. Stern often models career wear, but in this casual image she personifies the light-hearted freedom from constraint and effortless confidence in her own feminine attractiveness that Boucher depicted, time and again. So long as a woman like Tracie Stern exists, the reawakening of man’s ardour for beauty, and of his capacity to be ennobled by fancy and imagination, will always remain possible.

THE NEOCLASSICAL ERA

THE NEOCLASSICAL ERA

Lorna Roberts and Emma, Lady Hamilton

Few women’s lives testify to the epoch-making power of femininity as vividly as does that of Emma, Lady Hamilton (1765–1815). Born poor at a time when Britain was still dominated by class consciousness, and social mobility was frowned upon, Emma’s preternatural beauty enabled her to move freely in aristocratic circles, and eventually to do the unthinkable—i.e., to marry into the nobility. George Romney, the well-known English portrait painter, was utterly obsessed with her, and made a career of depicting Emma in every classical guise imaginable (and sometimes even as herself). Lady Hamilton also came to have tremendous influence with the King of Naples, had a meeting with the illustrious German poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and eventually became the mistress of Lord Nelson, England’s most revered naval hero and the man who dealt Napoléon a decisive defeat on the high seas.

The painting shown here, titled Lady Hamilton as a Bacchante and dating from 1792, is not by Romney but by the French artist Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun. As Lady Hamilton’s biographer notes, at this point Emma “had put on weight and was now more a goddess than a nymph.” But though her weight continued to increase steadily throughout her life, it never threatened her universally-acknowledged status as “the most beautiful woman in Europe.” Two centuries later, the striking features and magnificent figure of Lorna Roberts, currently Britain’s most beautiful plus-size model (“faux-plus” Sophie Dahl notwithstanding), vividly evoke the memory of Lady Hamilton at the height of her glory.

THE ROMANTIC ERA

THE ROMANTIC ERA

Liis and Doña Isabel Cobos de Porcel

“Everyone knows the sensuous Isabel de Porcel,” writes Pierre Gassier, “regarded as the embodiment of womanhood in the full bloom of her beauty.” Despite all the changing fashions in art and portraiture, critics have never failed to be overwhelmed by the subject of this famous painting by Francisco Goya, dating from 1805. I have had the pleasure of seeing this painting in real life, in the National Gallery in London, and standing before it, one is quite overcome by the Doña’s physical presence. One also notices fascinating little details, like her plump hands, dimpled at the knuckles, and the beginnings of a double chin. Insecure women of today may be certain, however, that in her lifetime the Doña felt not the slightest need to “control her appetite,” but indulged every desire she ever had, knowing that beauty such as hers could never be diminished.

Discussing this canvas in his definitive, four-volume study of Goya, José Gudiol is rapturous in his praise:

The portrait of Isabel Cobos is one of the most universally admired of Goya’s paintings, as much for the richness of the forms and the beautiful harmony of colour as for the physical attraction of the sitter…The fine and generous features of this beautiful woman, her open expression and the exuberance of the flesh tones harmonize completely with her fair hair and the black mantilla and reddish jacket set against the greenish background. There is a real relation between the material of the paint and the actual substance of the flesh, and any of those indefinite or half-finished effects that still continue to appear in certain details of his works are abandoned. In this painting Goya’s realism prevails over his expressionist tendencies.

The significance of the last point cannot be overstated. Goya’s is a nightmarish world peopled by grotesque beings—some human, some not—who struggle to avoid being engulfed up by the darkness in which the painter surrounds them. However, in this one instance, the power of his subject’s beauty was such that even he, Francisco Goya, was diverted from his instinctively morbid inclinations, and compelled to pay unequivocal homage to her lavish charms. The Doña’s vitality pierces through the dark veil of his interpretive consciousness as surely as her rose-coloured satin shines through the dark folds of the mantilla.

So why does she form a perfect fit with Liis, who, apart from sharing her full lips and opulent proportions, differs from her in certain physical details? Because both women display the calm vanity that is the hallmark of all true goddesses. Critics have observed, without disparagement, how “proud, self assured,” even “haughty” the Doña appears, how she “surveys the world without fear…her eyes are brilliant in defiant challenge.” Liis expresses a comparably powerful sense of self in many of her best photographs, an absolute security in her own attractiveness, and a challenge to her viewers that they prove worthy of her attention.

THE FIN DE SIÈCLE

THE FIN DE SIÈCLE

Sophie Dahl and Lillian Russell

I do not exaggerate when I say that Sophie Dahl’s severe recent weight loss is regrettable to the point of being tragic. Prior to this, she truly was among the most beautiful of women, and a modern Paris would likely have judged in her favour over any other living goddess. Foremost among her charms, Sophie boasts the most perfect doll’s features since those of Lillian Russell (1861–1922), a famous turn-of-the-century American singer and actress, and the loveliest woman of whom we have photographic record. The resemblance between the two is pronounced.

In his biography of Miss Russell, Parker Morell records the impression that she made upon a contemporary theatergoer:

There was nothing wraithlike about Lillian Russell; she was a voluptuous beauty, and there was plenty of her to see. We liked that. Our tastes were not thin, or ethereal. We liked flesh in the [18]90s. It didn’t have to be bare, and it wasn’t, but it had to be there.

Oscar Tschirky recounts the experience of seeing her eating in a New York restaurant:

I was captivated by this fleeting glimpse. I remember the smooth flow of her blue gown, the exotic effect of her golden hair, but most of all the banked-down fire that smouldered in her beautiful face.

Best of all, Morell also confirms that, for most of her life, Russell felt no need to torture herself with dieting:

With a blithe contempt for the consequences, she continued for years in the habit of eating her way through such fourteen-course dinners as left even the voracious Diamond Jim Brady sated. Pounds and pounds were accumulating on her already stuffed figure. But what of it?

Though she weighed over 180 lbs. at the height of her career, Lillian Russell was not an exception in the annals of beauty, but the norm. So were each of the other paragons of loveliness whose images appear here. Plus-size beauty was beauty in every era prior to our own. It is only through today’s politically-motivated, androgynous standards that an attempt has been made to overturn this timeless aesthetic. However, as a new century dawns, we are ready to right ourselves again, and to find beauty not in the bone-and-plastic caricatures that flicker across our television screens, but in the immortal images that remain graven in all our hearts.